Mission Continues: Translating Military Values into Public Service

Veterans don’t stop serving when they hang up the uniform- they just change the mission. Across city halls, state agencies, and federal offices, former service members are bringing battlefield-tested leadership, data-driven decision-making, and unwavering accountability to public administration. Their unique blend of structure, teamwork, and adaptability is reshaping how government tackles today’s toughest challenges- from emergency response to social equity. In a time when public trust and efficiency are in short supply, veterans are proving that the same values that win wars can also rebuild the civic fabric.

Veterans bring a strong sense of mission-first thinking, something ingrained through years of structured service, into civilian roles. This mindset allows them to focus on outcomes rather than personal gain, a perspective that is especially valuable in government settings. In my transition from active duty to working with the Department of Veterans Affairs, I’ve found that the same principles that guided unit cohesion and mission success in the Army - accountability, purpose, and adaptability - are directly applicable to leading projects and teams in civilian agencies.

Leadership in the military is not about rank alone; it’s about responsibility to people and objectives. Veterans understand how to lead under pressure, make data-informed decisions, and remain mission-aligned regardless of the environment. These abilities are critical for government initiatives that often require coordination across departments, adherence to regulatory frameworks, and responsiveness to shifting community needs. According to a study by the RAND Corporation, veterans often outperform their civilian counterparts in leadership roles due to their training in decision-making and crisis management under duress¹.

Adapting Military Problem-Solving to Civil Challenges

One of the most transferable military skills is the ability to assess complex problems and develop actionable solutions, even with limited resources. Veterans are trained to operate in uncertain environments, often using the Military Decision-Making Process (MDMP) to analyze scenarios, weigh risks, and execute plans. This structured yet flexible approach can be highly effective in local government settings where administrators must juggle competing priorities, budget constraints, and public accountability.

For example, when I began coordinating outreach programs for underserved veterans in rural areas, I approached the task using a modified version of the MDMP. We conducted a terrain analysis - in this case, mapping service deserts - and developed phased initiatives to increase benefits enrollment. The same operational planning that once helped coordinate convoys through conflict zones was now facilitating access to healthcare and pensions. Veterans trained in logistics, intelligence, or operations often bring a systems-level view that is invaluable in addressing multifaceted issues like homelessness, emergency preparedness, or transportation planning².

Building Trust Through Shared Service Values

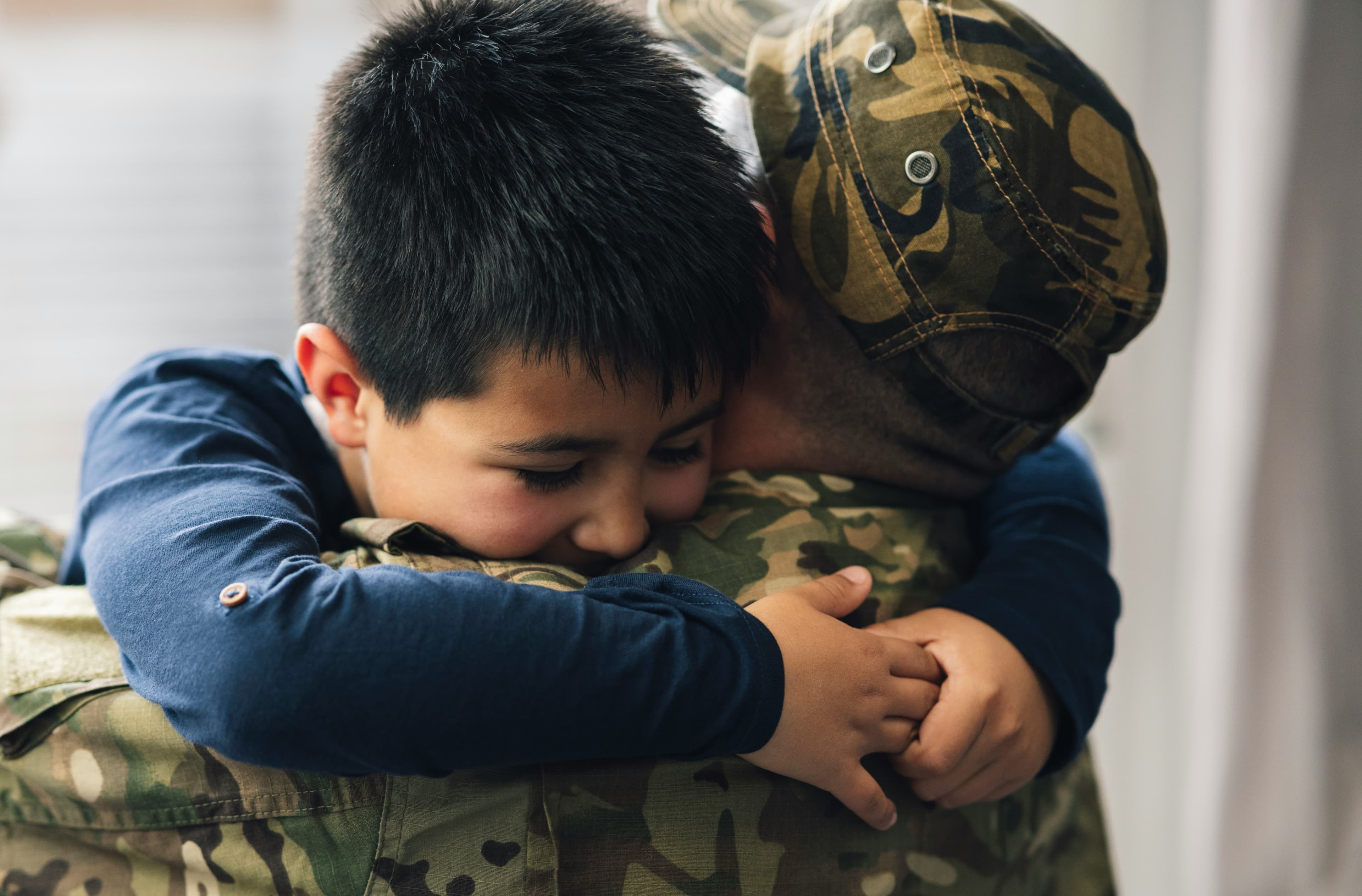

Trust is a core currency in both military units and civilian governance. Veterans understand the importance of integrity, follow-through, and keeping commitments - qualities that are essential for public-facing roles. When constituents see veterans serving in government, it often reinforces confidence in institutions. This is particularly true for veteran-specific services, where peer-to-peer trust can determine whether someone seeks help or continues to struggle in silence.

In my current role, I’ve seen how veterans working as benefits officers, housing coordinators, or mental health liaisons often become informal ambassadors of government service. Their credibility is rooted in shared experience rather than titles or credentials. According to research from the Lincoln Network, veterans are more likely to be trusted as public servants, especially among other veterans and military families³. This dynamic can be leveraged to improve program uptake, reduce bureaucratic friction, and foster stronger civic engagement.

Creating Veteran Pipelines into Civil Service

While the value veterans bring is clear, there is still a gap in structured pathways that support their transition into meaningful government roles. Many veterans are unaware of how their military occupational specialties translate into civilian job classifications, particularly within local and state agencies. Bridging this gap requires active collaboration between veteran service organizations, universities with public administration programs, and government HR departments.

Programs like the Department of Labor’s Veterans’ Employment and Training Service (VETS) and the VA’s Non-Paid Work Experience (NPWE) initiative provide some entry points, but more targeted mentorship and workforce development efforts are needed. Municipalities and other local agencies should consider establishing veteran fellowship programs, offering internships tailored to former service members, and providing resume translation workshops. These initiatives not only assist veterans but also strengthen institutional capacity with talent that is already mission-driven and trained in organizational discipline⁴.

Maintaining a Service Ethic Beyond the Uniform

Leaving active duty doesn’t mean leaving behind the core ethic of service. For many veterans, the desire to contribute remains, but the mechanisms change. Government service offers a meaningful continuation of that commitment, allowing veterans to protect and uplift communities just as they once protected their fellow citizens in uniform. The transition can be challenging, but when properly supported, it results in a workforce enriched by resilience, clarity of purpose, and operational know-how.

Veterans often find that their sense of identity, purpose, and mission can be rekindled through roles that have tangible impact. Whether it’s improving emergency response systems, ensuring equitable access to public health resources, or modernizing legacy information systems, veterans bring a practical, no-nonsense approach to government work. Agencies that recognize and cultivate this mindset stand to benefit from employees who are not only competent but also deeply committed to the communities they serve⁵.

Conclusion: Service Beyond the Battlefield

When duty changes uniforms, the mission doesn’t end - it evolves. Veterans carry with them a deep well of experience, not just in tactics and logistics, but in purpose-driven leadership. By integrating this experience into civilian institutions, particularly within government, we can create more agile, responsive, and mission-oriented agencies. The key is to recognize that service is not confined to the battlefield. It lives on in council chambers, social services offices, and planning departments, wherever the call to serve continues.

To those in government looking to build stronger institutions, and to veterans seeking to continue their calling, the message is simple: the mission continues. And with the right support, veterans will keep showing up, not in formation, but in purpose, ready to lead again.

Bibliography

RAND Corporation. “The Deployment Life Study: Longitudinal Analysis of Military Families Across the Deployment Cycle.” Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2014.

Department of Veterans Affairs. “Military Decision-Making Process and Its Application in Civilian Institutions.” Washington, DC: VA Office of Policy and Planning, 2021.

Lincoln Network. “Veterans in Public Service: Trust, Representation, and Opportunity.” Washington, DC: Lincoln Network Policy Brief, 2022.

U.S. Department of Labor. “Veterans’ Employment and Training Service (VETS).” Accessed April 2024. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/vets.

Partnership for Public Service. “A Call to Duty: The Value of Veterans in Government.” Washington, DC: Partnership for Public Service, 2020.

More from Military

Explore related articles on similar topics