The City Is the Case: What “SVU” Can Teach Planners and Policymakers

For a show that’s been on the air for over two decades, Law & Order: SVU has done more than dramatize New York’s crimes, it’s mapped the city’s soul. Week after week, detectives sprint through subway tunnels, brownstones, luxury condos, and housing projects. The skyline shifts, the tech updates, but the city itself stays the same: chaotic, compressed, endlessly alive.

Look closely, and SVU starts to feel less like a cop show and more like an accidental course in urban studies. Its locations aren’t just backdrops. They’re evidence. The show captures how lighting, zoning, and transit shape the moral geography of the city: who feels safe, who gets seen, and who slips through the cracks.

At its core, SVU is about design as destiny. Olivia Benson may be chasing criminals, but she’s also navigating decades of policy, from broken windows policing, to gentrification, to public housing neglect, that built the very conditions for her cases.

Good planning, like good detective work, depends on empathy and observation. Both ask the same question: how do we build a city that protects without dividing, that shelters without hiding, that truly sees everyone?

The City as Character

From the first "dun dun" of the opening theme, SVU insists that New York is not just a setting, it’s a character. The show’s geography is sprawling but familiar: courthouse steps, narrow alleys, mid-block walk-ups. Each episode functions like a cross-sectional slice of the city, connecting a Park Avenue penthouse to a Queens shelter in forty-two minutes.

Urban planners talk about “density” as a measure of efficiency. SVU shows it as a condition of empathy. The city’s compactness ensures that stories and people collide. The wealthy and the vulnerable live close enough to see one another, and the result is friction. The show’s most enduring theme is that proximity doesn’t guarantee understanding; it merely makes ignorance harder to sustain.

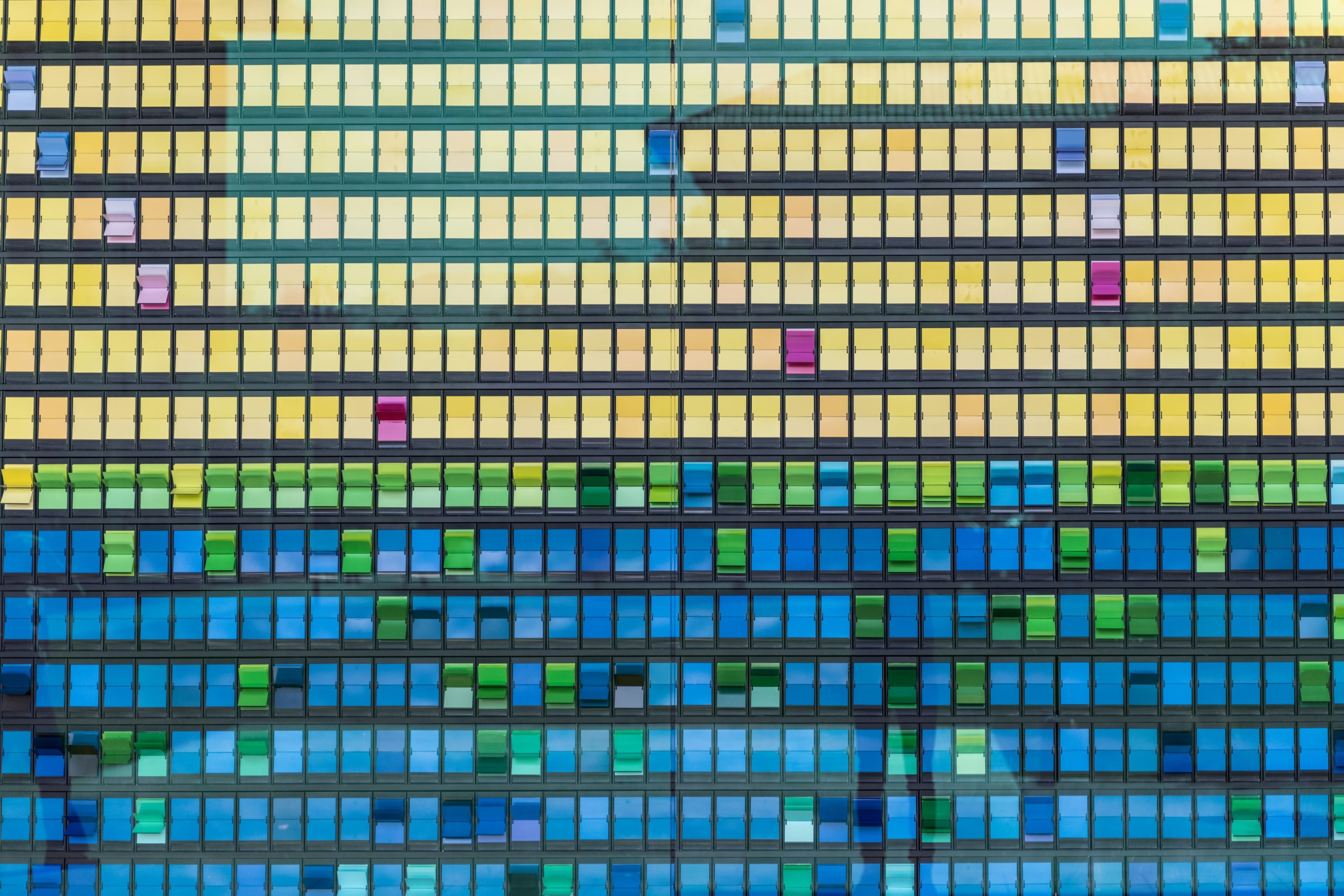

That’s a lesson echoed in the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s 2021 report on Infrastructure Disparities and Equity in American Cities, which found that the uneven distribution of public investment reinforces patterns of visibility and neglect. In SVU, this inequity is rendered visible. Gleaming midtown towers and crumbling Bronx playgrounds share the same narrative world, forcing viewers to confront the physical and moral geography of inequality.

Lighting and the Geography of Safety

Few shows are as obsessed with lighting as SVU. The difference between safety and danger, in its world, often comes down to whether the streetlight works. The show’s cinematography dramatizes what Jane Jacobs called “eyes on the street,” the idea that active, well-lit public spaces deter harm simply by ensuring people can see and be seen.

That visual truth has empirical backing. A 2008 review in Campbell Systematic Reviews by Brandon Welsh and David Farrington found that improved street lighting consistently reduces crime, not just by increasing visibility, but by signaling investment and care. SVU seems to intuit that logic: its episodes linger on flickering bulbs and darkened alleys as visual shorthand for municipal neglect.

Lighting, in this way, becomes policy. The HUD report makes a similar point: physical cues like lig

Read-Only

$3.99/month

- ✓ Unlimited article access

- ✓ Profile setup & commenting

- ✓ Newsletter

Essential

$6.99/month

- ✓ All Read-Only features

- ✓ Connect with subscribers

- ✓ Private messaging

- ✓ Access to CityGov AI

- ✓ 5 submissions, 2 publications

Premium

$9.99/month

- ✓ All Essential features

- 3 publications

- ✓ Library function access

- ✓ Spotlight feature

- ✓ Expert verification

- ✓ Early access to new features

More from Infrastructure

Explore related articles on similar topics